The reduction to C Major principle is an improvising system I created to gain the possibility to play upon every kind of chord by just “using” the C Major scale: CDEFGAB.

I do not pretend that this could be a sort of Columbus’ egg, or something that has not been invented before. It’s just another method, a different approach. I do not want to replace the traditional solutions and rules, but perhaps try to give a different vision of things. It can also be used for harmonization or riffing, beside pure improvisation purposes.

The main idea came from my lazyness. I’m a very lazy person. When I started to study music it was like climbing a mountain high till the Moon. For a single scale, there is one mode for each degree of the scale, for each mode at least five possible fingerings per octave to learn. To master a single scale it may take a whole life. Too much for me!!! I needed to take things back to the roots and completely change my way!

I’ve always noticed (and I hope you did too) that there are only seven note names, while commonly accepted sounds are twelve per octave. Even if we go beyond the tempered system, there are no further note names than C D E F G A B. There are all sorts of sharps and flats, but we do not have any R or S or Q. Why? They must be somehow special and magic. The new system has to be built ground up from there!

So, everything begins here: C Major scale on a C Major triad. Quite simple, huh?

Some points to observe:

- When we actually make music, it’s not mandatory to play excercises or forcefully insert in phrasing what we studied the day before as pure mechanical training

- Nodoby forces us to play a complete scale from beginning to end, nor to follow the order of the notes

- Using a ready-to-use scale born centuries ago for purposes that are obviously different from the song we’re about to play could even work, but, is it really what we want? Is that our ART?

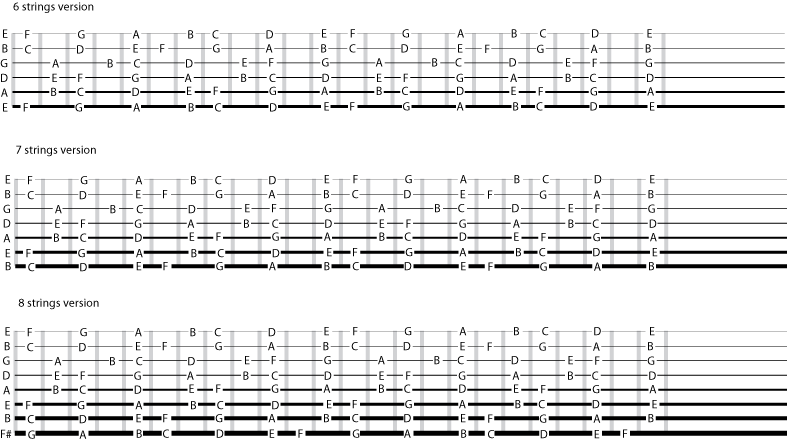

The main input came from point #2. So, if we want to focus on the C Major scale, we need to know where those notes are on our instrument, without chaining them in sequences, shapes or patterns. The only technical requirement needed to play with my method is that: you just need to be able to hit any of the seven notes (in any octave) at any moment! No more scales, modes or fingerings!! Just ONE THING!! Here is a fretboard scheme that I’ve recycled from an old Allan Holdworth’s video, adapting it to the modern 7 and 8 strings instruments too:

The main part comes now, obviously… what are we supposed to do when the backing chord is not a C Major triad anymore? Here comes the revolution (or involution, to be precise).

Normally, the classic music theory wants to give things a name. So, when G-B-D are played simultaneoulsy, they must be named G Major. Or, another example, if E-G-Bb-Db are played at once, they must be called E diminished. But… why? The only purpose that I found (by consuming my brain) is that such “short names” should be easy to use when communicating with other musicians playing with you. But people don’t hear the names, they just hear the result of note stacking, the actual chord itself!

So, to improvise the “short name” information (=the normal name of the chord) involves a decoding process: unless things are very simple, it’s very quick to remember for example that C = stacking of C-E-G. But, we could come to the case that our mates says: “ehi, the next chord is a C#maj11 with a Gmaj9/b5 in the lower octave”… and now????

The solution is the simplest. Instead of “decoding” what the name of the chord means, we will use the exact notes it’s made of. Obviously, the chord (of any type, with any fancy ultracomplex notation) will be made of two or more sounds picked from C D E F G A B and some of them will be eventually sharpened or flattened. There is no other possibility, as we discovered!!!

Hence, to play on our “misterious chord” we just need to “deform” the standard C Major scale with the sharps and flats present in it, and again “dance” on the fretboard schemes. That’s all. Let’s make some examples:

E first inversion:

Something more drastic… can you figure out a name for that chord on the bass staff?

The sonic solutions that comes out by blindly applying this method are sometimes well known (even if we don’t give them a name), sometimes are completely new and suprising, and the poorly trained ears could even find them… out of tune!! Oh, that’s amazing for we, the arstists!!

Another great possibility has been given to us by the mighty J.S. Bach (…yes, Him!!) some centuries ago. He invented the Equal Temperament, so after Him notes with different names had actually the same sound (ex. C# = Db, Ab = G# and so on). This opens up new mathematical combinations. The two previous examples may be played also this way:

The most important thing is that these “scales” are not intented to be practiced or learned anyway: you must be able to “deform” the C Major scale on the fly, based on the analysis of the backing chord.

More investigations and eventually some video is coming… stay tuned!